To be a visual artist.

You are lying on the grass in the sun. Above is a beech tree. A slight wind lifts the lighter branches and turns the leaves. From a distance this constant movement of the leaves makes it look as if green snow is falling in front of the tree’s green surface-just as once silvery snow seemed to fall in front of the grey cinema screens. Through half-closed eyes you gaze up. They are half-closed because you are watching intently. One bough extends further than the others. It is impossible to count the number of leaves on it. The blue sky which you see through and arround these leaves is like the whiteness of paper round the letters of words. The distribution of the leaves against the sky seems far from arbitrary. You find yourself wondering whether it might not be possible to explain their sequence as one can explain the sequence of letters and words in a book. Then you discover an image which, like a good teacher, gives direction to your confused thinking. Everything-you begin to say to yourself-in order to archieve existence at all, must pierce the very centre of a target; anything which misses that centre simply does not exist. But a teacher’s words after he has gone often prove a disappointment. So you are left puzzling how the bough above you can be said to represent the entire Spring….Thinking like this you may be a philosopher, but I don’t think you’re a visual artist.

You are lying with your head on your carefully folded jacket. The tree, you calculate, must be a good twenty meters tall. You can discover any buds? You screw up your eyes. There are none left. Things must be at least a fortnight further advanced than at home. It’s lower, of course, and protected by the hills. Then you try to see if you can distinguish the inconspicuous flowers. The bough is too high and the light is too bright.You remember that during famines men ate beech fruit. After all, the beech belongs to the same family as the sweet chestnut; and pigs are turned into beech woods in the autumn. But then pigs eat anything. Your eye travels along the bough. Its shape is like the outline of a horse’s hind leg seen from the side. You are becomming sleepy, but as you look up you imagine throwing a rope over that bough. You are not longer thinking, you are drifting, and your eyes are almost shut. Yet the palms of your hands and insides of your knees go tense at the memory of climbing along such twisting branches as a child. For you the parts of the tree are there to master in one way or another….but not through drawing.

Idly and every so often you close your eyes. Then the image of the pattern of the leaves remains for a moment before fades, imprinted on your retina, but now deep red, the color of the darkest rhododendron. When you re-open your eyes the light is so brilliant that you have the sensation of it breaking against you in waves, reminding you of how small an island you are in the grass. You are aware of the children playing around you, and by some association too quick for you to notice-although you will remember it in retropspect-you marvel at how many birds a tree ca hide. At dusk, when a man approaches, a flock of forty or fifty starlings can scatter upwards from a single may tree to circle the sky once more; like painted birds on a fan suddenly opened and then slowly shut again. The tree is full of incidents, imagined and remembered. But for you, above all, this tree exists in time, and its size and its green-ness and the reasoning of the man who originally planted it, no less than the reasoning of the man who may order it to be felled, all remind you of this fact. Suddenly you notice that the sky is not a uniform blue. There, above the tree, is a vertical streak of paler blue,branching out at ist top end in several directions. In fact, it`s like a tree itself, you say. Then you watch it change into a lion´s head….You are using your eyes-like a poet perhaps; but not like a painter.

You lie there. You can smell the grass. You are more than usually concious of the warmth of the sun. You have the sensation that you are stretched across the world and so can feel the curve of the earth. Nothing about the tree surprise you. You look at it as an actor may look at the auditorium. And your drama? Your arm is round another waist; a hand strokes through your hair. You may be anybody, bit at the moment you see the tree as only a lover sees it. The tree is an X marking a spot for you both.

You do not look at the tree. What sense is there in lying down if you have to use your eyes? You half listen to the wind. The leaves sound like sand beeing tipped. When you wake you look up very warily. You see green, blue, green mixed with dirty white. The green has taken every trace of yellow out of the blue. That fact is certain. Everything else is confused. Without concentrating very hard and, as if with your hands, you begin to sort out what you can see. Imitating the skill of the flowersellers who know exactly which sprig to put with which, you learn to distinguish the swags of foliage, allotting each to ist own branch and to its own proper position in space. You begin to test the angles of the branches, like a fitter, not like a mathematician. You do your best to belittle that tree: to reduce it to a tangible size and simplicity. You close your eyes again. But now you are concentrating.You are thinking of graphic marks. How can they adapt themselves to admit such a tree? How can they keep such a tree in its proper place? Gradually you are able to imagine it appearing as a brushed-in image. When you open your eyes to look at the actual tree you try your hardest to see it as you have just imagined it. But you can´t. It remains there towering against the sky.You belittle it again. Close your eyes once more. Adapt the tree that is only an image. Then open your eyes to check. The image is getting close,but the beech still towers and shimmers above you.Again and again. And so you may lie until it is dark…and be a visual artist.

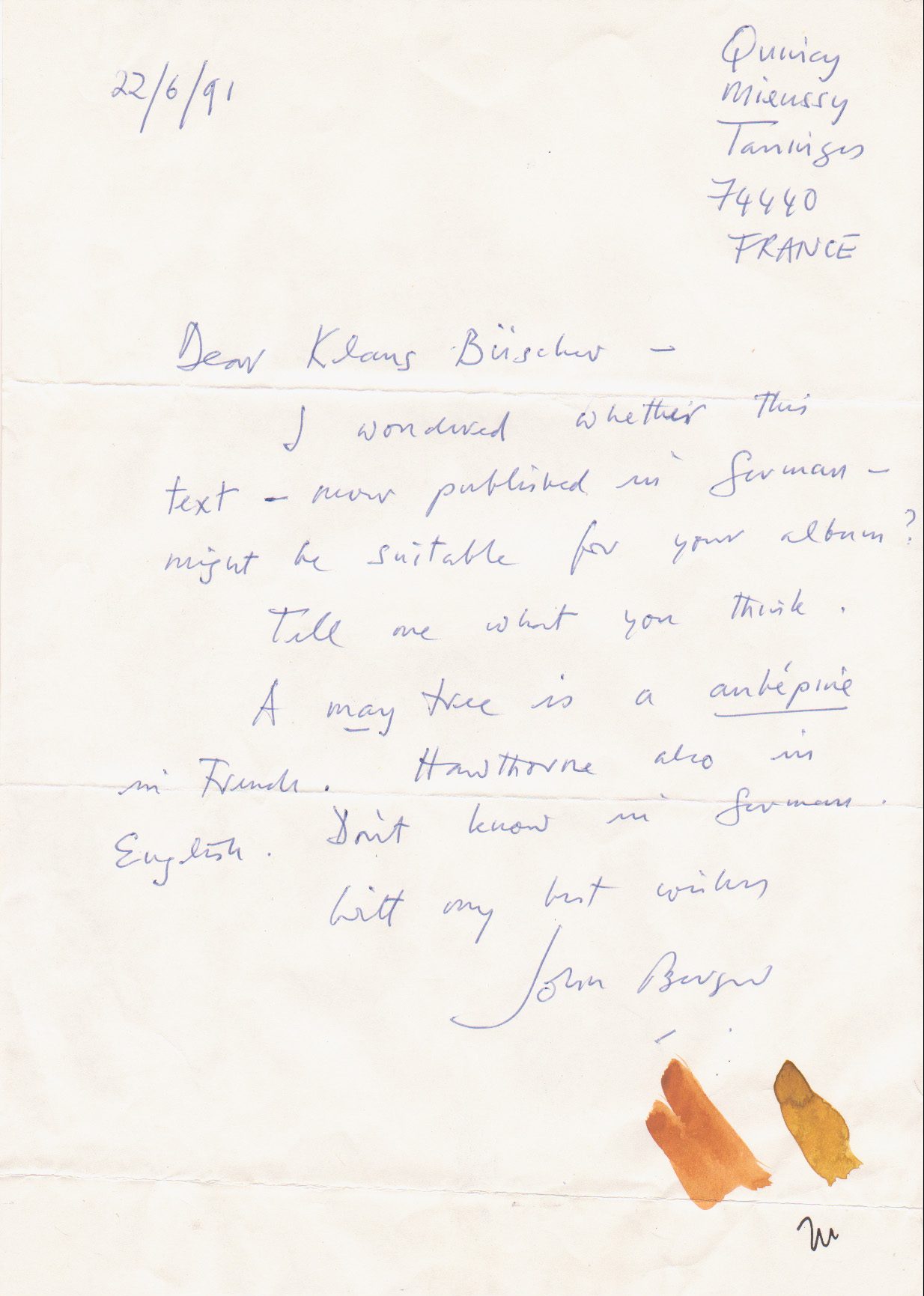

John Berger

Ein bildender Künstler sein

Du liegst in der Sonne im Gras, über dir eine Buche. Ein sanfter Wind hebt die leichten Äste und bewegt die Blätter. Aus der Ferne sieht diese unaufhörliche Bewegung der Blätter aus, als falle grüner Schnee vor der Oberfläche des Baumes, genauso, wie es einst schien, dass silbriger Schnee vor der grauen Kinoleinwand fällt. Durch halbgeschlossene Augen starrst du hoch. Sie sind halbgeschlossen, weil du gespannt schaust. Ein Ast streckt sich weiter als die anderen. Es ist unmöglich, die Blätter an ihm zu zählen. Der blaue Himmel, den du durch die Blätter und außen herum siehst, ist wie das Weiß des Papiers rund um die Buchstaben von Wörtern. Die Anordnung der Blätter gegen den Himmel gesehen erscheint weit weg von Willkür. Du überlegst, ob es nicht möglich ist, deren Ordnung zu erklären, so wie man die Abfolge von Buchstaben und Wörtern in einem Buch erklären kann. Dann entwickelst du ein Bild, welches wie ein guter Lehrer eine Richtung in dein konfuses Denken bringt. Jedes Ding, sagst du laut zu dir selbst, muss, um überhaupt zu existieren, den Kern einer Idee treffen. Alles, was dieses Zentrum nicht trifft, existiert einfach nicht. Aber das Wort des Lehrers erweist sich oft als Enttäuschung, nachdem er uns verlassen hat. So stehst du allein da, rätselnd, wieso es heißt, der Ast dort über dir stünde für den gesamten Frühling. Bei einer solchen Überlegung bist du vielleicht ein Philosoph, aber ich denke kein bildender Künstler.

Du liegst mit deinem Kopf auf deiner sorgfältig gefalteten Jacke. Der Baum, schätzt du, muss gut zwanzig Meter hoch sein. Kannst du irgendwelche Knospen entdecken? Du schaust. Da sind keine. Die Natur müsste hier wenigstens 14 Tage weiterentwickelt sein als Zuhause, weil es hier natürlich flacher und durch die Hügel geschützt ist. Dann versuchst du zu erkennen, ob du die Blüten unterscheiden kannst. Der Ast ist zu hoch und das Licht zu hell. Du erinnerst dich, dass Menschen während der Hungersnöte Bucheckern aßen. Nach allem gehört die Buche zur selben Familie wie die Esskastanie; Schweine wurden im Herbst in die Wälder getrieben, aber Schweine fressen ja auch alles. Dein Blick wandert den Ast entlang. Seine Form ist wie der Umriss des Hinterbeines eines Pferdes von der Seite gesehen. Du wirst müde, aber als du aufblickst, stellst du dir vor, ein Seil über den Ast zu schleudern. Du denkst nicht mehr, du lässt dich treiben und deine Augen sind beinahe geschlossen. Doch sind die Handflächen und Innenseiten deiner Knie angespannt von der Erinnerung an das Klettern auf verschiedenen Ästen in deiner Kindheit. Für dich sind die Teile des Baums dazu da, sie in irgendeiner Form zu meistern….aber nicht durch zeichnen.

Träge und immer wieder für längere Zeit schließt du die Augen. Dann bleibt das Bild der Anordnung der Blätter für einen Moment eingeprägt auf deiner Netzhaut, aber nun tiefrot wie die Farbe des dunkelsten Rhododendron, bevor es verschwindet. Wenn du die Augen wieder öffnest, ist das Licht so gleißend, dass du meinst, es breche auf dich in Wellen ein, was dich daran erinnert, was für eine kleine Insel im Gras du bist. Du nimmst die Kinder wahr, die um dich herum spielen, und durch eine plötzliche Assoziation – zu schnell für dich sie wahrzunehmen – obwohl du dich zurückblickend erinnern wirst, wunderst du dich, wie viele Vögel ein Baum verstecken kann; zur Dämmerung, als ein Mann erscheint und ein Schwarm von vierzig oder fünfzig Staren von einem einzelnen Rotdorn aufflog, um den Himmel noch einmal zu umfliegen, wie gemalte Vögel auf einem Fächer, der plötzlich geöffnet und dann langsam wieder geschlossen wird. Der Baum ist voller Ereignisse, gedachter und erinnerter. Für dich aber existiert der Baum vor allem in seiner Geschichte, in seiner Größe, seinem Grün und den Gedanken des Mannes, der ihn ursprünglich gepflanzt hat und nicht weniger auch an den Mann, der einst befehlen mag, ihn zu fällen; alles erinnert dich an diese Tatsache. Plötzlich bemerkst du, dass der Himmel nicht gleichmäßig blau ist. Dort über dem Ast ist ein senkrechter Streifen von fahlerem Blau, der sich zur Spitze hin verästelt und in mehreren Richtungen ausläuft. In der Tat, es sieht aus wie ein Baum, sagst du. Dann beobachtest du, wie es sich in einen Löwenkopf verwandelt. Du benutzt deine Augen vielleicht wie ein Dichter, aber nicht wie ein Maler.

Du liegst da. Du kannst das Gras riechen. Dir ist mehr als sonst die Wärme der Sonne bewusst. Du hast das Gefühl, dass du dich quer über die Welt ausstreckst und so die Erdkrümmung spüren kannst. Nichts am Baum überrascht dich. Du schaust ihn an wie ein Schauspieler in den Saal sieht. Und dein Drama? Dein Arm umfasst eine andere Hüfte, eine Hand streicht dir durchs Haar. Du magst irgendeiner sein, aber in diesem Moment siehst du den Baum, so wie nur ein Liebender ihn sieht. Der Baum ist eine Markierung, ein Punkt für euch beide.

Du schaust nicht auf den Baum. Was macht es für einen Sinn zu liegen und doch seine Augen gebrauchen zu müssen. Mit halbem Ohr hörst du auf den Wind. Die Blätter klingen, als würde Sand ausgeschüttet. Wenn du wach bist, schau sehr vorsichtig hoch. Du siehst Grün, Blau, Grün gemischt mit Schmutz, Weiß. Das Grün hat jede Spur Gelb aus dem Blau gezogen. Das ist sicher. Alles andere ist durcheinander. Ohne sich stark zu konzentrieren und als ob du es mit deinen Händen tun würdest, beginnst du das auszusortieren was du sehen kannst. Die Geschicklichkeit des Blumenverkäufers imitierend, der genau weiß welcher Zweig zu welchem passt, lernst du zu unterscheiden, die Masse des Blattwerks zu ordnen, jedes Blatt zu seinem Ast und zu seiner richtigen Position im Raum. Du fängst an, die Gabelung der Äste zu untersuchen, wie ein Monteur und nicht wie ein Mathematiker. Du tust dein Bestes, den Baum zu verkleinern, ihn zu reduzieren auf eine greifbare Größe und Einfachheit. Du schließt deine Augen wieder, aber nun konzentrierst du dich. Du denkst an grafische Merkmale. Wie können sie sich ergänzen, um einen derartigen Baum zu ergeben? Wie können sie den Baum an seinem Platz halten? Allmählich bist du in der Lage, ihn dir als gemaltest Bild vorzustellen. Wenn du deine Augen öffnest, um auf den echten Baum zu sehen, versuchst du dein Bestes, ihn genauso zu sehen, wie du ihn dir gerade eingebildet hast. Aber du kannst es nicht. Er aber bleibt da stehen, sich in den Himmel türmend. Du vereinfachst noch einmal. Schließ deine Augen wieder. Stell dir den Baum als Bild vor. Dann öffne die Augen, um es noch einmal zu überprüfen. Dein Bild wird ähnlicher, aber die Buche türmt sich noch und schimmert über dir, immer wieder. Und so magst du liegen bleiben, bis es dunkel ist…und ein bildender Künstler sein.

John Berger

Übersetzung ins Deutsche: Jan Pelkofer